Barrel aging beer offers us a way get creative while providing unique, small-batch experiences for our customers. As brewers, however, do we really know what’s going on inside those barrels while we let them sit?

Let’s take a look under the microscope to get a better idea.

When it comes to most beers, the goal is to avoid growth of anything that’s not brewer’s yeast. Wild yeast and bacteria can provide unwanted and unexpected changes in flavor and fermentation profiles. Even when we pitch a mixed culture that includes other yeast (such as Brettanomyces) or bacteria (such as Lactobacillus), we typically know exactly which organisms are in there.

Barrel aging, on the other hand, forces us to be a little more open to different yeast and bacteria strains. Microbes that would normally be considered taboo have a welcome home in the barrel. Nevertheless, it’s still important to understand these bugs and to know the difference between the good, the bad, and the ugly. It’s also crucial to understand how these microorganisms work and how to keep them in check, so we can prevent the infection of other beers—especially any core brands.

Besides that cautionary aspect, barrel aging beer takes some patience. Knowing about the wild yeast and bacteria involved can help us understand why it’s important to let barrels sit—and for how long.

Bacteria: The Usual Suspects

Let’s start off with the types of bacteria that will most likely take up residence in a barrel.

Acetobacter is probably one of the most recognizable when it comes to flavor profiles. These bacteria create acetic acid by metabolizing ethanol into acetate, and barrels that have them create a vinegar-like aroma and flavor.

That may seem unappealing, but the presence of acetate early on isn’t always a death sentence for a barrel. Below, we go deeper into microbe cycles and the importance of maturation time, but for now it’s worth noting that letting the beer sit for longer in the barrel can give any acetic acid a chance to decrease in intensity.

Meanwhile, it’s also true that low levels of acetic acid can enhance and accentuate the character of certain beer styles that feature acidic flavor. Thankfully, there are many different types of barrel-aged beer styles, and as brewers we have the flexibility to use different flavors—essentially creating whatever we want from the flavor profile of a single barrel or set of barrels.

Another bacterium that’s commonly present in barrels is Gluconobacter. As part of the Acetobacter family, Gluconobacter works with Acetobacter to create those vinegar-like flavors. That’s not all, though: Gluconobacter also has a knack for making less-desirable vegetal and parsnip flavors—and those are difficult to mask if these bacteria stick around over the lifetime of the barrel.

Of course, we can’t forget to acknowledge lactic acid–creating bacteria such as Lactobacillus and Pediococcus. Familiar friends when it comes to sour beers, they tend to make their presence known—if they’re there—later in the bacterial cycle.

Most of the time, the brewer is happy with the soft sourness that Lactobacillus tends to create. Pediococcus is less reliable, sometimes producing too much diacetyl. In addition, high levels of Lacto and Pedio can cause haze and ropiness in the beer if high levels are present after barrel aging.

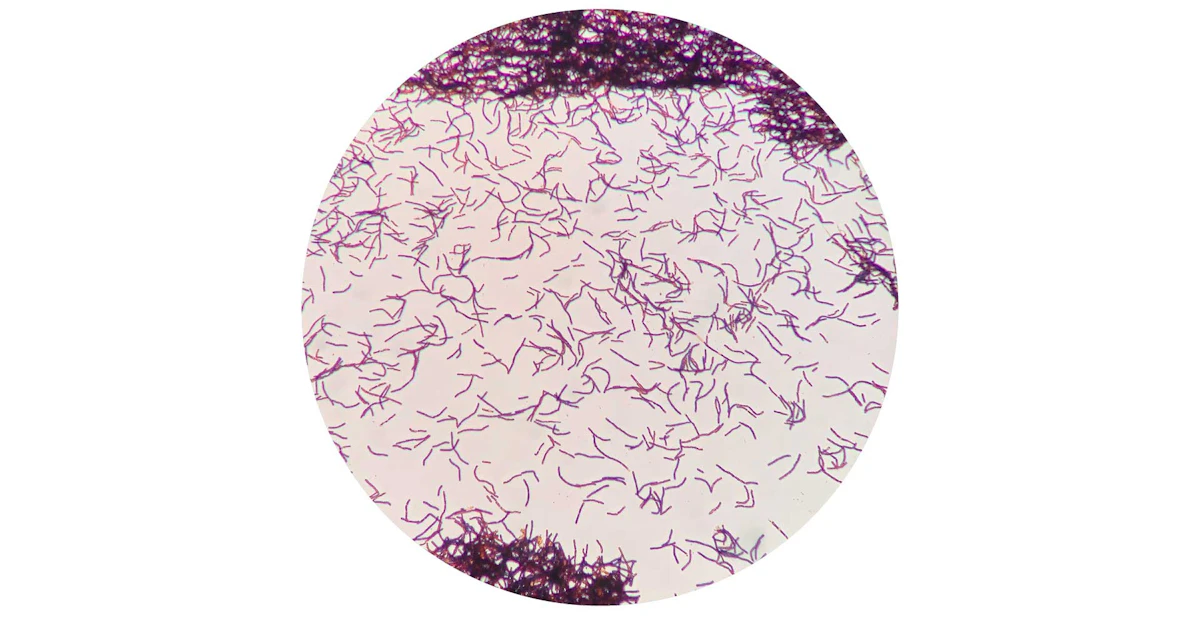

Photo: Jamie Bogner

Wild Yeast

Now let’s move on to the other division of microbes: yeast.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae have their place in the barrel microbe cycle, but the majority of yeast present will be non-Sacch. These strains can include Brettanomyces, Candida, and Pichia. In general, we know these strains for their rustic, earthy, barnyard-like aromas—especially in barrel-aged beers that feature Brett, whose diverse expression can include pleasant floral notes and earthy flavors.

As with the vinegar flavors, however, it’s possible to have too much of a good thing—those barnyard or horse-blanket notes tend to be more desirable at lower levels. Plus, they can create additional haze and sediment in the final product.

Of course, there are many other off-flavors that can come from wild yeast. These include acetone, which tends to occur when temperatures are too high or when there’s too much headspace oxygen in the barrel. If acetone is present early, it’s unlikely to mellow with time in the same way that vinegar and barnyard flavors may.

Maturation

Besides knowing what’s inside the barrels, it’s important to understand maturation and why it’s important to give all those microbes time to do their thing.

The time can vary widely—anywhere from perhaps six months to multiple years. Having regular sensory checks can help you get a better idea of where the barrel is in its cycles and estimate how much longer it may need to sit.

However, here’s a quick summary.

The First Month

During the first month, the intense flavors from acetic-acid bacteria and non-Sacch yeast have the greatest impact. It’s best to not even bother with performing sensory on the barrels right away—disappointment is likely.

Six Months

At six months, things really start to get interesting. Lactic-acid bacteria and Saccharomyces yeast take over the majority of sugar consumption. Depending on how prevalent the initial non-Saccharomyces yeast and bacteria were, those early vinegar and/or barnyard flavors may dissipate or fade into the background. The final flavor profile ultimately depends on the ratio of each type of yeast or bacteria present.

And Beyond…

The next six months and afterward see further maturation, and this is also when Brettanomyces tends to play a greater role. By now, it should be clear whether a barrel is going to keep some of the early, undesirable off-flavors. The hope is that things are relatively clean and that the barrel can continue to mature into your target profile.

Lactobacillus

Sensory

Sensory sampling becomes most important after those first six months—sampling too early won’t give you a realistic picture of what the final barrel will taste like. Consistent tastings after the first six months can give you a better idea of when you may want to rack or blend.

Remember: It’s important to keep things sanitary when sampling from barrels. The last thing you want in the later stages is to introduce any additional yeast or bacteria to inhibit the progress you’ve made so far. It’s best to spray the nails and the outside of the barrel generously with isopropyl alcohol and to wear gloves anytime you pull a sample.

It might make sense to have one person leading the sampling and performing regular checks, but it’s ideal to convene a full sensory panel before blending. That way, you can pull in other people who may pick up on off-flavors hiding in the background. Having this final sensory consensus can help you decide whether all the barrels are desirable or whether there are some that you should avoid because of off-flavors.

It always hurts to have to dump beer, especially when you’ve already invested a year or more into its maturation. Ultimately, however, it hurts more to put out an inferior product. The ideal blend includes only the best of the best from the barrels.

Sanitation

Barrel aging microbes can get funky, to say the least, so it’s important to have heightened awareness of cleaning practices not only when sampling but whenever you’re handling barrel-aged liquid. Preventing cross-contamination in the tank farm is critical. In general, it’s a good idea to have some separation—for example, keeping barrels in a separate area of the brewery and using a color-coding system for equipment that touches only barrel-aged beer.

It’s also worthwhile to deploy more intense cleaning practices after a barrel-aged beer circulates through the cellar or packaging lines. An autoclave or pressure cooker is ideal for small components and gaskets, to ensure the death of any microbes that touched those parts.

This thorough cleaning is especially important because some of these yeast and bacteria create a biofilm on surfaces they touch—that’s when microbes grow and create a thicker layer. Higher temperatures and longer contact times when cleaning vessels and hoses are essential to eradicate those layers. Note that some of these bacteria are both hop- and acid-tolerant—so there’s no guarantee that the IPA going into the tank next will have enough IBUs to kill off any residual bacteria.

Finlly, I’d strongly recommend pairing a microbiological-testing program with your barrel-aging program. That way, you and your team can identify the bacteria and yeast that show up in those barrels. If you know for sure what’s in there, then it’s much easier to track down any contamination—for example, if something escapes and infects a core brand.

Successful barrel aging requires more monitoring and cleaning, but it’s worth it for the complex, unique beers that wood and time can produce in concert with different yeast and bacteria. Knowing what’s growing in there—and when—can help you get the most out of your time and labor, helping you to achieve, or even surpass, your creative vision.